The Heels of Ya’akov

How to Acquire the Attribute of Yosef ha-Tzaddik

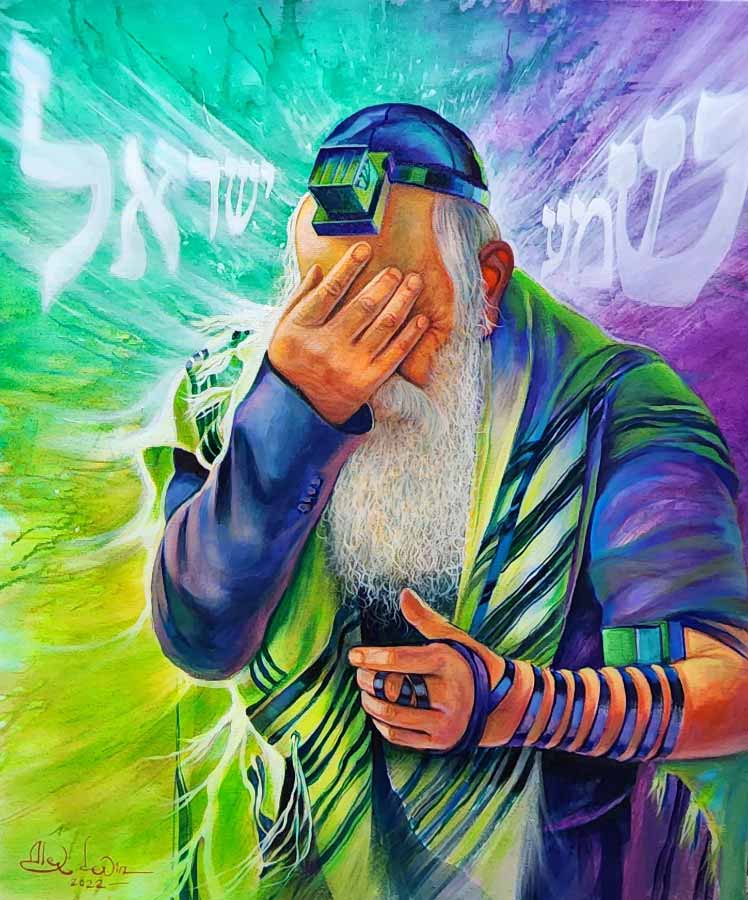

In last week’s article Ya’akov’s Fear in Going Down to Egypt, we learned that through the strength of his character, specifically his shemirat einayim, Yosef was able to break the tumah of immorality that filled the land of Egypt. As a result of his unprecedented strength of character in this area, his father Ya’akov was able to descend to Egypt by the command of Hashem and dwell there safely without compromising his own personal kedushah.

This is all very interesting from an historical perspective, but what about us today? We are also living in a type of Egypt, i.e. in the midst of unparalleled tumah that the world has perhaps never before experienced. Therefore, from a very practical standpoint, we must ask the inevitable question, Is it even possible for us today to accept upon ourselves this middah and to teach others to do so? After all, Ya’akov Avinu was only able to descend into Egypt after Hashem assuaged his fear by essentially telling him, ‘If Yosef is found there, he has already broken the impurity, and you will be able to be shomer einayim‘ (see Bereshit 46:3-4). But what about us? Number one, we’re no Ya’akov; and number two, the world today has no leader, as far as we know, who can even begin to approach the kedushah of Yosef. So, is it all just completely hopeless or is there a way for us to succeed even in the midst of our Egypt? (As we work our way through this study, keep in mind that although we will be speaking in terms of shomer einayim and kedushat ha-brit, which are phrases generally associated with men, the main point in this study also pertains to women in the broader perspective of modesty.)

As is known, Yosef is identified or associated with the sefirah of yesod, meaning that he completely epitomized kedushat brit. But what about his father Ya’akov? Is he associated with any particular sefirah? And if so, which one? It is written in Michah 7:20: תִּתֵּן אֱמֶת לְיַעֲקֹב חֶסֶד לְאַבְרָהָם (You gave truth [emet] to Ya’akov, chesed to Avraham). Just as Avraham elevated himself to the level of the sefirah of chesed, Ya’akov did so to the level of the sefirah of emet. But which sefirah is that? It is the sefirah known as tiferet. What is the unique light of tiferet? The word is usually translated as beauty or splendor, but that doesn’t really help us to understand what it is. In short, tiferet is in the ‘middle column’ between chesed on the right, and gevurah on the left. Tiferet combines, so to speak, these two somewhat opposite attributes. Whereas chesed is all about freely giving and being kind, gevurah is all about withholding, judging and being strict. Tiferet is able to take these two, somewhat opposite middot and synthesize them into a unified whole. It’s not about watering down the chesed by mixing in a little bit of gevurah or mitigating the gevurah by adding in a little bit of chesed. No. It’s a completely new middah that takes each strength into account and utilizes them together at their full strength simultaneously. If chesed is compared to white and gevurah is compared to black, then tiferet is a picture drawn with a black pencil on a white background or alternatively, a picture drawn with a white pencil on a black background. The point is that tiferet is not gray.

Now, Ya’akov elevated himself to the level of the sefirah of tiferet. As we’ve said, tiferet is associated with beauty, splendor, or harmony, and we’ve also seen that it’s associated with emet. All of this is true. But there’s another angle to understanding tiferet that we haven’t touched upon yet, and in many ways, this other angle may actually describe the essence of Ya’akov more than any other single word. And what is that?

Avraham Avinu testified about himself that he was עָפָר וָאֵפֶר, dirt and ash (Bereshit 18:27). Similarly, it is said about Yitzchak that, as a result of his willingness to be slaughtered on the altar by his father Avraham, אפרו צבור על גבי המזבח, his ash is piled up on top of the altar (Rabbeinu Bachya on Bereshit 22:10). But with regard to Ya’akov, something even more extraordinary is stated. Of all people, Bila’am praised Ya’akov with these words (Bamidbar 23:10): מִי מָנָה עֲפַר יַעֲקֹב (Who can count the dirt of Ya’akov?). In other words, although Avraham was likened to dirt and ash, and Yitzchak was likened to a pile of ash, both of these ideas are measurable quantities. On the other hand, the amount of dirt associated with Ya’akov is literally immeasurable. Who can measure it? That’s the dirt of Ya’akov.

What is this dirt? It is the middah of the heel, as it is written (Tehillim 119:112): נָטִיתִי לִבִּי לַעֲשׂוֹת חֻקֶּיךָ לְעוֹלָם עֵקֶב (I have inclined my heart to perform your statutes, always, heel [eikev]). What does this mean? Our commentators have followed a few different approaches. Some have taken the reference to eikev as a metaphor for roads or paths, i.e. that which the heel walks on. In other words, ‘Whatever road I may find myself on in life, I will always follow your ways.’ Others take eikev as indicating the ‘end of the body’, i.e. to the end of one’s life, such as, ‘I will keep your ways, always, to the end of my life.’ The Noam Elimelech brings out a nuance, perhaps a little deeper. He writes, פירוש עיקר השגחתי היתה לעשות החוקים ע”י מדת העקב היא הענוה (The explanation of the verse is that ‘my main concern was to perform the statutes through the middah of the heel, which is humility’). This accords with what Shlomo ha-Melech taught in his wisdom (Mishlei 22:4): עֵקֶב עֲנָוָה יִרְאַת יְיָ (The result [or ‘effect’] of humility is the fear of Hashem). The word here for ‘result’ is also eikev. In other words, humility is likened to the heel, the lowest part of one’s physical body. And that’s the deeper reason why Ya’akov was called Ya’akov (Bereshit 25:26): וְאַחֲרֵי־כֵן יָצָא אָחִיו וְיָדוֹ אֹחֶזֶת בַּעֲקֵב עֵשָׂו וַיִּקְרָא שְׁמוֹ יַעֲקֹב (And afterward, his brother came out and his hand is holding on to the heel [eikev] of Esav, and he [or ‘He’] called his name ‘Ya’akov’). Is this pasuk coming to teach us an interesting piece of historical trivium surrounding the birth of our father Ya’akov? Not really. Rather, the pasuk is coming to teach us that Ya’akov will, in the end, subdue Esav through the middah of the heel, i.e. through his exalted humility, through the power of the sefirah of tiferet. Therefore, although we may say that Ya’akov was the essence of emet (which he was) or that he was the epitome of the middle column between chesed and gevurah (which he was), both of these traits led to the real essence of his character, the one attribute that underscored everything he did and everything he stood for, i.e. his humility. (For further insight on this point, see Raise Your Voice Like a Shofar which we published two weeks ago.)

As a side point, we also learn from this that if someone wants to work on developing humility, he’ll first need to work on acquiring these two attributes of chesed and gevurah. This is the deeper meaning of the pasuk in Bereshit 25:27: וְיַעֲקֹב אִישׁ תָּם יֹשֵׁב אֹהָלִים (And Ya’akov was a simple man, dwelling in tents). Although the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah 63:10 says that the ‘tents’ are a reference to the beit midrash of Shem and the beit midrash of Ever, on a deeper level, the Zohar ha-Kadosh in Terumah 175b tells us that the ‘tents’ are a reference to chesed and gevurah. This is, in fact, why Ya’akov is called a ‘simple man’ [ish tam]. He is tam in that he is shalem, i.e. ‘whole’, having encompassed himself in the two attributes of chesed and gevurah. And what attribute did Ya’akov first need in order to accomplish that? He needed to love emet. On the one hand, he loved Hashem’s Torah, which is emet (Tehillim 119:142): צִדְקָתְךָ צֶדֶק לְעוֹלָם וְתוֹרָתְךָ אֱמֶת (Your righteousness is eternally righteous and Your Torah is emet). And on the other hand, he loved speaking emet, even about himself to himself, and even when that emet may have been unpleasant and difficult for him to hear, as it says (Tehillim 15:2): הוֹלֵךְ תָּמִים וּפֹעֵל צֶדֶק וְדֹבֵר אֱמֶת בִּלְבָבוֹ (Walking in simplicity [tamim], and doing justice and speaking emet in his heart). The same is true of us today. If we want to develop humility to become an aspect of Ya’akov, we’ll need to work on developing chesed and gevurah, and to do that, we’ll need to develop a love of emet in the two areas just explained.

Now we return to our initial question. Since we are not at the level of Ya’akov and since there’s no world leader today who has the kedushah of Yosef, is there any hope for us today?

The answer is found in this pasuk (Bereshit 48:2): וַיַּגֵּד לְיַעֲקֹב וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּה בִּנְךָ יוֹסֵף בָּא אֵלֶיךָ וַיִּתְחַזֵּק יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיֵּשֶׁב עַל־הַמִּטָּה (And he told Ya’akov, and he said, Behold your son Yosef comes to you. And Yisrael strengthened himself and sat up in the bed). But before we explain how this pasuk answers our question, we need to have in mind another important pasuk (Bereshit 41:44): וַיֹּאמֶר פַּרְעֹה אֶל־יוֹסֵף אֲנִי פַרְעֹה וּבִלְעָדֶיךָ לֹא־יָרִים אִישׁ אֶת־יָדוֹ וְאֶת־רַגְלוֹ בְּכׇל־אֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם (And Pharaoh said to Yosef, I am Pharaoh, and [yet] without you, no one will be able to lift his hand or his foot in all the land of Egypt).

Commenting on that pasuk, R’ Nachman of Breslov writes (Likutei Moharan 10:10): כִּי בִּלְעֲדֵי בְּחִינַת יוֹסֵף שֶׁהוּא בְּחִינַת הַצַּדִּיק אִי אֶפְשָׁר לְהַעֲלוֹת וּלְהָרִים הַיָּדַיִם וְהָרַגְלַיִם (For without the aspect of Yosef, who is the aspect of the Tzaddik, it is impossible to elevate or raise up the hands or the feet). Yosef is the aspect of the Tzaddik. What does this mean? Who is the Tzaddik? It is the soul of Moshe Rabbeinu, the soul of Mashiach, whose soul (in some fashion or another) rests upon the greatest of all the tzaddikim in every generation, the one individual who, if everything else comes together, would be fitting to become the actual Mashiach. Yosef is the aspect of that Tzaddik. So what? R’ Nachman is teaching an amazing truth here. And what is that? Based on the deeper understanding of Bereshit 41:44, no one can really accomplish anything without connecting to the Tzaddik of his generation. Don’t be so surprised by this. It is, after all, one of the central pillars of Breslov chasidut. The goal and challenge, of course, is to find this Tzaddik, for it’s not such a simple thing. He’s not going to be walking around with a sign on his head that says, ‘I’m the Tzaddik of the generation.’ Rather, he’ll be hidden and surrounded by much controversy, for the klipot will do all they can to prevent people from drawing hear to him. Nevertheless, even if one has not yet merited to find the Tzaddik in his generation, he need not fall into despair for he should also be connecting himself to the teachings, i.e. to the soul, of this same Tzaddik in previous generations (such as R’ Nachman himself, the Baal Shev Tov, the Arizal, the Rambam, and R’ Shimon bar Yochai, just to name a few).

So what do we learn about Ya’akov? He was lying in bed unable to raise or elevate his hands or his feet. He was bedridden and very ill. Yet what happened when Yosef ha-Tzaddik entered the room? Immediately, Ya’akov strengthened himself and sat up! That’s the power of the Tzaddik, and this story with Ya’akov is a fulfillment of the deeper meaning of the pasuk which says that no one can lift up or raise his hands or feet without Yosef. This is what R’ Nachman was explaining in L.M. 10:10.

Now it’s time to tie it all together. As we saw earlier, Bereshit 48:2 says יוֹסֵף בָּא אֵלֶיךָ (Yosef comes to you). When does the aspect of Yosef come to a person? When that person has developed the aspect of Ya’akov. Read that again, because that’s the entirety of this article. But if you want, we’ll spell it out. When we work on our humility, which is the aspect of becoming like Ya’akov, then the ability to be shomer einayim, which is the aspect of Yosef, will automatically come to us. It’s really that simple. If we want to be successful at guarding our eyes (or working on any aspect of modesty), then we need to work on our humility. We need to become a shtickle piece of dirt for others to walk over. If we want a nice example to recall in times of need, think of the holy Tanna R’ Tarfon. Many stories are told of his exceptional humility, but perhaps the most well known story is that he used to get down on all fours to act as a human footstool for his elderly mother when she needed to get in and out of bed.

Of course, we shouldn’t stop there. Although it may be a good place to start, humility doesn’t end with how we treat our parents. After all, don’t we pray these words—וְלִמְקַלְלַי נַפְשִׁי תִדּוֹם וְנַפְשִׁי כֶּעָפָר לַכֹּל תִּהְיֶה (May my soul be silent to those who curse me, and may my soul be like dirt to everyone)— three times every day? Yup, we sure do.