It is taught in Kabbalah that Hashem has three hands: יָד הַגְּדוֹלָה [yad ha-gedolah, the great hand], יָד הַחֲזָקָה [yad ha-chazakah, the strong hand], and יַד הָרָמָה [yad ha-ramah, the exalted hand]. What are these hands? They are spiritual lights, i.e. the sefirot in the upper world of Atzilut. Yad ha-gedolah corresponds to chesed on the right, yad ha-chazakah to gevurah on the left, and yad ha-ramah to tiferet in the middle. Chesed refers to loving-kindness, gevurah to strict judgment and tiferet to an attribute that incorporates these two in a composite light of mercy and truth. These hands are mentioned in the Torah with respect to the Exodus; therefore, if we study some of these references, we will enhance our understanding of the Exodus.

We shall begin with the yad chazakah since it is the hand most referred to throughout the Torah. The first time it is mentioned is at the burning bush. Hashem said to Moshe (Shemot 3:19): אֲנִי יָדַעְתִּי כִּי לֹא־יִתֵּן אֶתְכֶם מֶלֶךְ מִצְרַיִם לַהֲלֹךְ וְלֹא בְּיָד חֲזָקָה (I know that the King of Egypt will not let you go without a yad chazakah). In order to understand what is being said, we need to approach this verse in two steps. The first step is to focus on the words in the Torah. Hashem wasn't telling Moshe that Pharaoh would let Yisrael go only because of a 'strong hand' or a 'mighty hand' or something like that. These translated words are ambiguous; however, the Hebrew words are specific and precise. Hashem was telling Moshe that Pharaoh will only let them go through His yad chazakah, not through His yad gedolah or His yad ramah. The second step to comprehend what Hashem was actually telling Moshe is to insert the correct meaning of yad chazakah into the verse, i.e. the only way Pharaoh would let them go is if he and his nation would get bashed with judgment after judgment.

The next mention of yad chazakah is in Shemot 6:1: וַיֹּאמֶר יְיָ אֶל־מֹשֶׁה עַתָּה תִרְאֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶעֱשֶׂה לְפַרְעֹה כִּי בְיָד חֲזָקָה יְשַׁלְּחֵם וּבְיָד חֲזָקָה יְגָרְשֵׁם מֵאַרְצוֹ (And Hashem said to Moshe, Now you will see what I will do to Pharaoh, for with a yad chazakah he shall send them out, and with a yad chazakah he will drive them out from his land). This has the same meaning as the verse in Shemot 3:19. The next use is in reference to the mitzvah of tefillin (Shemot 13:9): כִּי בְּיָד חֲזָקָה הוֹצִאֲךָ יְיָ מִמִּצְרָיִם (For with a yad chazakah Hashem brought you out from Egypt). There are many more verses in the Torah that mention this hand, and if the reader is inclined to read them all (Devarim 4:34, 5:15, 6:21, 7:8, 7:19, 9:26, 11:2, etc.), he will see that each one reiterates the same point, i.e. that Hashem brought Yisrael out of Egypt with His yad chazakah, i.e. through the plagues and judgments against the Egyptians.

Let's now look at the yad ramah (Shemot 14:8): וַיְחַזֵּק יְיָ אֶת־לֵב פַּרְעֹה מֶלֶךְ מִצְרַיִם וַיִּרְדֹּף אַחֲרֵי בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל יֹצְאִים בְּיָד רָמָה (And Hashem strengthened the heart of Pharaoh, King of Egypt, and he chased after B'nei Yisrael, and B'nei Yisrael went out with a yad ramah). Rashi explains the meaning of yad ramah as that they came out בִּגְבוּרָה גְּבוֹהָה וּמְפֻרְסֶמֶת (with lofty and openly-displayed gevurah). Rashi isn't taking gevurah in its Kabbalistic sense, but rather according to its plain meaning, i.e. 'might, power'. He is describing the enthusiastic and victorious way in which the Jews left Egypt.

On a deeper level, this yad ramah is a reference to the sefirah of tiferet, i.e. Hashem's hand in the middle column. After Hashem struck Egypt with His attribute of gevurah, i.e. strict judgment, He brought out Yisrael with the attribute of tiferet, i.e. mercy [רַחֲמִים, rachamim]. Hashem did not bring them out of Egypt with chesed. He brought them out with rachamim. And why was rachamim needed? The nation of Yisrael was also guilty and needed to do teshuvah in order to merit freedom. After all, they had sunk below forty-nine levels of impurity during their years of servitude in Egypt (Zohar Chadash Yitro 39a): דְּוַדַּאי יִשְׂרָאֵל כַּד הֲווֹ בְּמִצְרַיִם אִסְתְּאָבוֹ וְאִתְטְנָפוֹ גַּרְמֵיהוֹן בְּכָל זִינֵי מְסָאֲבוּ עַד דַּהֲווֹ שָׁרָאן תְּחוֹת אַרְבָּעִים וְתֵשַׁע חֵילֵי דִּמְסָאֲבוּתָא (For definitely, when Yisrael was in Egypt, it made itself impure and filthy from all manner of impurity so much so that it dwelt below, i.e. were subjugated by, forty-nine powers of impurity). Therefore, they were in serious danger of annihilation themselves if it hadn't have been for the promises that Hashem had made previously to the Patriarchs (Devarim 7:7-8).

The yad ramah is mentioned in one other place in the Torah (Bemidbar 33:3): וַיִּסְעוּ מֵרַעְמְסֵס בַּחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם לַחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן מִמׇּחֳרַת הַפֶּסַח יָצְאוּ בְנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּיָד רָמָה לְעֵינֵי כׇּל־מִצְרָיִם (And they traveled from Rameses in the first month, on the fifteenth day of the first month; the morning after the Pesach B'nei Yisrael came out with a yad ramah in the sight of all Egypt). We have here the same terminology describing the same event, i.e. the yad ramah relates to the actual exit of Yisrael from Egypt the morning after Pesach.

Now let's discuss the yad gedolah, the hand in the right column, the attribute of chesed. There is only one explicit reference to this hand in the Torah. The Song of the Sea is prefaced with these words (Shemot 14:31): וַיַּרְא יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת־הַיָּד הַגְּדֹלָה אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה יְיָ בְּמִצְרַיִם וַיִּירְאוּ הָעָם אֶת־יְיָ וַיַּאֲמִינוּ בַּיְיָ וּבְמֹשֶׁה עַבְדּוֹ (And Yisrael saw the yad gedolah which Hashem did against Egypt, and the people feared Hashem and they had emunah in Hashem and in Moshe His servant). Similar to how he explained yad ramah, Rashi explains yad gedolah according to its plain meaning: אֶת הַגְּבוּרָה הַגְּדוֹלָה שֶׁעָשְׂתָה יָדוֹ שֶׁל הַקָּבָּ"ה (the great might that the hand of the Holy One, blessed be He, did). However, Rabbeinu Bachya explains the deeper meaning:וטעם הגדולה לפי שהיא שואבת מן החסד כי לכך נזכרה בשירה בלשון ימינך (The reason [it is called] ha-gedolah is because it is drawn from chesed, for this is why it is described as 'Your right hand' in the Song [of the Sea]). He is specifically referencing Shemot 15:6: יְמִינְךָ יְיָ נֶאְדָּרִי בַּכֹּחַ יְמִינְךָ יְיָ תִּרְעַץ אוֹיֵב (Your right hand, Hashem, glorious in power, Your right hand, Hashem, shatters the enemy). This is the yad gedolah, the attribute of chesed.

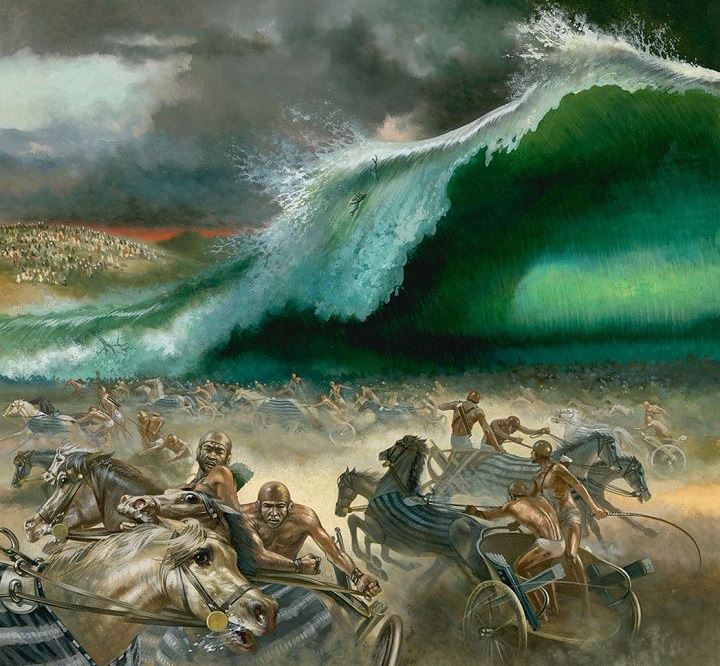

The events at the sea put the spotlight on Hashem's love for His people. The wondrous miracles that He performed for them at the sea were unparalleled in the history of the world. To list just a few, the sea was divided into separate paths for each tribe, the floor of the seabed turned into a beautiful mosaic similar to those found on the floor in kings' palaces, the walls of the sea produced fresh water and sweet fruits, everyone attained to the level of a prophet as they sang in unison with Moshe Rabbeinu, and even the babies inside their mothers' wombs sang. Although we can catch a glimpse of Hashem's love for Yisrael, how was Hashem's treatment of the Egyptians also an act of chesed? On the surface, this seems paradoxical.

Perhaps the answer is similar to what we learn in the Torah about the rebellious and wayward son [בֵּן סוֹרֵר וּמוֹרֶה, ben sorer u'moreh]—see Devarim 21:18-21. The Gemara goes through great lengths in chapter eight of Sanhedrin to explain the details of the boy's crimes: somewhat gluttonous, drinks too much wine and engages in small acts of theft. That doesn't sound terrible enough to justify the death penalty. And, in fact, under normal circumstances prescribed by the Torah, they don't amount to a capital crime. Not only that, but the specific conditions required to legally convict and execute a boy for being a ben sorer u'moreh are so numerous, specific and narrow in scope that it is stated that there never was and never will be anyone executed for this crime (Sanhedrin 71a): בן סורר ומורה לא היה ולא עתיד להיות ולמה נכתב דרוש וקבל שכר (There has never been nor will there ever be a ben sorer u'moreh; therefore, why is it written? So that one may study and receive reward).

But why does the Torah state that he must suffer the death penalty? R' Yosi ha-Galili gives the answer (Sanhedrin 72a): הגיעה תורה לסוף דעתו של בן סורר ומורה שסוף מגמר נכסי אביו ומבקש למודו ואינו מוצא ויוצא לפרשת דרכים ומלסטם את הבריות (The Torah foresaw the end of the ben sorer u'moreh's attitude, that he would eventually exhaust the property of his father and he would seek to maintain his habit and won't find [the wherewithal to do so], then he'll go out to the crossroads and rob people). As explained by the commentators, he won't just stop at robbery, but he'll do whatever he deems necessary, even murder and desecration of Shabbat, to satisfy his lusts.

What's the answer to our question? The Gemara continues: אמרה תורה ימות זכאי ואל ימות חייב שמיתתן של רשעים הנאה להם והנאה לעולם ולצדיקים רע להם ורע לעולם (The Torah said, let him die while he is innocent and not die while he is guilty, for the death of the wicked is a benefit to them and a benefit to the world, but for the tzaddikim, it is bad for them and bad for the world). The Torah of the ben sorer u'moreh teaches us that, under certain unique circumstances, a punitive death penalty can be an act of chesed, i.e. a benefit, to the person being executed, and all the more so to the rest of the world. By drowning the Egyptians in the sea, Hashem, so to speak, was putting them out of their misery and doing them a benefit. They were never going to do teshuvah and they would never stop their fruitless quest to recapture the Jews. All they were doing was feeding their own miserable existence with even more misery and adding more misery to the whole world.

One last point before concluding: although we stated above that there was only one explicit reference to the yad gedolah in the Torah, there are indirect references to it. In many places where we read that Hashem brought B'nei Yisrael out of Egypt with signs and wonders, it adds that it was with הַיָּד הַחֲזָקָה וְהַזְּרֹעַ הַנְּטוּיָה (the yad chazakah and the stretched out arm). We have already learned about the yad chazakah, but what is this stretched out arm? It is the hand stretched out to accept sinners. As we mention during tachanun on Monday and Thursday mornings: הַפּוֹתֵחַ יָד בִּתְשׁוּבָה לְקַבֵּל פּוֹשְׁעִים וְחַטָּאִים (Who opens a hand for teshuvah to accept criminals and sinners). But, how do we know this is the right hand, the yad gedolah? It says so explicitly during the selichot prayers leading up to Yom Kippur: נַחְפְּשָׂה דְּרָכֵינוּ וְנַחְקֹרָה וְנָשׁוּבָה אֵלֶיךָ כִּי יְמִינְךָ פְּשׁוּטָה לְקַבֵּל שָׁבִים (Let us examine our ways and analyze and return to You, for Your right hand is extended to accept penitents). Even during times of harsh judgments when Hashem's attribute of din, i.e. the yad chazakah, seems to have the upper hand, He still extends out His right hand, the yad gedolah, the hand of chesed and loving-kindness to accept those who sincerely acknowledge and regret their transgressions.

With respect with the Exodus, we can understand this 'stretched out arm' in one of two ways. First, it teaches that although Hashem blasted Egypt with His yad chazakah; nevertheless, He extended to them an opportunity of forgiveness if they would have done teshuvah. Second, it teaches that while Hashem was bringing judgment upon Egypt for the despicable and treacherous way that they treated the Jews, the nation of Yisrael was not innocent either. As we saw above, they had sunk below forty-nine levels of impurity during their years of servitude in Egypt and needed to do teshuvah themselves.

In summary, the process of freeing Yisrael from slavery came about via three distinct attributes. First, the yad chazakah, the attribute of gevurah (strict justice), was needed to break Egypt's will to let Yisrael leave. Second, the yad ramah, the attribute of tiferet (mercy), was needed because the Jews were liable for punishment and needed mercy in order to leave Egypt. Third, it required the yad gedolah, the attribute of chesed (loving-kindness). This hand was used in two ways. It was stretched out to Jew and Egyptian alike when Hashem was striking the Egyptians with the plagues, to receive those who sincerely did teshuvah. And it was also used on the Egyptians to put them out of their misery once and for all when they pursued the Jews into the sea.

Perhaps now when we pray to Hashem for mercy to redeem His people from our current exile, which is the right and proper thing to do, we might consider praying also for the revelation of His love, which is by far a much more exalted attribute than mercy.

There is an expression that 'love is blind'. It's true. Love is blind, but mercy is not. Mercy is not blind for it must acknowledge, i.e. 'sin', transgression. Love, on the other hand, is truly blind. It is elevated above and precedes gevurah and tiferet, therefore, it has nothing to do with transgression at all.