Seeing the Points of Good in Each Jew

The story is told of the Tanna Elisha ben Avuyah who abandoned the ways of Hashem and became the heretic whom they called 'Acher' ['Other']. We won't go into the details of how he became a heretic for those who are interested can read the entire account in Chagigah 15a-16b. Rather, we want to focus on the behaviour of one of his foremost students, R' Meir, who continued to learn Torah from him even after he had abandoned the Torah. One Shabbat, R' Meir grabbed him from off his horse and dragged him to a synagogue. Things didn't go so well there for Acher, so R' Meir took him to another one, and then to another one, and to another one, and so on. In all, R' Meir took him to 13 different synagogues. No matter how much R' Meir tried to save his former teacher, Acher was unable to find the path of teshuvah.

After Acher's death, the Heavenly Court was in a quandary. On the one hand, they couldn't grant him life in Olam ha-Ba since he had forsaken the Torah, and yet on the other hand, they couldn't sentence him to Gehinnom either because all of the Torah that he had learned previously protected him from such a fate. Aware of what was going on in Heaven, R' Meir declared that when he would die, he would make sure that Acher was taken to Gehinnom. His rationale was that if Acher was able to enter Gehinnom, his soul would receive purification and then be able to enter Olam ha-Ba. R' Meir's success was evident to all, for immediately after R' Meir's death, smoke rose from Acher's grave. The smoke continued to rise for many years, until R' Yochanan came along, and promised to get him out of Gehinnom. Immediately after R' Yochanan's death, the smoke ceased from Acher's grave. Amazing but true, the once great Tanna Elisha ben Avuyah received his tikkun through R' Meir and R' Yochanan.

But the story doesn't end there. A few hundred years later, Eliyahu ha-Navi appeared to an Amora by the name of Rabbah bar Shila. Rabbah bar Shila asked Eliyahu what Ha-Kadosh baruch Hu was doing at that very moment. Eliyahu replied that He was repeating teachings from the mouths of all the Rabbis except from the mouth of R' Meir! Shocked, Rabbah bar Shila demanded an explanation. Eliyahu told him that it was because R' Meir learned Torah from Acher. Not satisfied with the way things were, Rabbah bar Shila justified R' Meir's behaviour and said (Chagigah 15b): רַבִּי מֵאִיר רִמּוֹן מָצָא תּוֹכוֹ אָכַל קְלִיפָּתוֹ זָרַק (R' Meir found a pomegranate; he ate the inside and threw away the peel). At that very moment, Ha-Kadosh baruch Hu began His discourse with these words: מֵאִיר בְּנִי אוֹמֵר (Meir, My son, says…).

We would like to postulate that the most astonishing part of this story is that for hundreds of years not a single great Sage, neither a Tanna nor an Amora, came to advocate on behalf of R' Meir. Not one. That is, not until Rabbah ben Shila focused on the good and became R' Meir's advocate. The flip side is equally amazing. All it takes to change the course of history for good, is for one person to be willing not only to look for and find the good in another Jew, but to speak it out even in the face of what could become tremendous opposition.

When Hashem appeared to Moshe Rabbeinu at the burning bush, we read the following (Shemot 3:7): וַיֹּאמֶר יְיָ רָאֹה רָאִיתִי אֶת־עֳנִי עַמִּי אֲשֶׁר בְּמִצְרָיִם וְאֶת־צַעֲקָתָם שָׁמַעְתִּי מִפְּנֵי נֹגְשָׂיו כִּי יָדַעְתִּי אֶת־מַכְאֹבָיו (And Hashem said, I have certainly seen [Ra'oh ra'iti] the oppression of My people who are in Egypt, and heard their outcry because of their taskmasters, for I know their pain). Why does Hashem use the double language of 'seeing', i.e. ra'oh ra'iti? Wouldn't a single mention of 'seeing' have been sufficient? Even though Hashem saw how Yisrael would, in short order, sin so egregiously with the Golden Calf; nevertheless, He also saw their good right now, and it was that good that He was focusing on in order to redeem them. In the words of the Midrash in Shemot Rabbah 3:2: וַיֹּאמֶר ה' רָאֹה רָאִיתִי. רָאִיתִי לֹא נֶאֱמַר אֶלָּא רָאֹה רָאִיתִי, אָמַר לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא, משֶׁה אַתָּה רוֹאֶה רְאִיָּה אַחַת וַאֲנִי רוֹאֶה שְׁתֵּי רְאִיּוֹת ('And Hashem said, Ra'oh ra'iti.' It doesn't say Ra'ati, rather Ra'oh ra'iti. Ha-Kadosh baruch Hu said to him, 'Moshe, you see one 'seeing'; I see two 'seeings'). The Midrash goes on to explain that even though Hashem foresaw the sin of the Golden Calf, it was irrelevant when it came to redeeming them now, as it says: אַף עַל פִּי כֵן אֵינִי דָּנָם לְפִי הַמַּעֲשִׂים הָעֲתִידִין לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶלָּא לְפִי הָעִנְיָן דְּהַשְׁתָּא כִּי שָׁמַעְתִּי אֶת צַעֲקָתָם אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁיָּדַעְתִּי מַכְאוֹבָיו שֶׁעֲתִידִים לַעֲשׂוֹת, הֱוֵי רָאֹה רָאִיתִי (Even so, I am not judging them according to future actions they are to do, rather according to the situation now, for I have heard their outcry even though I know their pain that they are to do in the future. This is ra’oh ra’iti).

This idea is elaborated upon in Likutei Halachot (Hilchot Eruvei Techumin 6:19); וְעִקַּר הַגְּאֻלָּה הִיא עַל-יְדֵי זֶה, עַל-יְדֵי שֶׁנִּתְעוֹרְרוּ רַחֲמָיו יִתְבָּרַךְ לְהִסְתַּכֵּל רַק עַל הַטּוֹב, בִּבְחִינַת רָאֹה רָאִיתִי (The essence of the geulah is through this, by awakening His mercies, may He be blessed, to look only upon the good, in the aspect of Ra'oh ra'iti). And since Hashem determined that He would look only on the good, the people became worthy of geulah.

Continuing in Likutei Halachot: וְכָל הַוִּכּוּחַ שֶׁהָיָה בֵּין ה' יִתְבָּרַךְ וּבֵין מֹשֶׁה בְּמַרְאֵה הַסְּנֶה הַכֹּל הָיָה בְּעִנְיָן זֶה כִּי עִנְיָן זֶה לְחַפֵּשׂ תָּמִיד הַטּוֹב שֶׁבְּיִשְׂרָאֵל וּלְלַמֵּד עֲלֵיהֶם זְכוּת תָּמִיד הוּא עִנְיָן גָּבֹהַּ וְעָמֹק מְאֹד מְאֹד (And the entire argument between Hashem, may He be blessed, and Moshe at the appearance of the bush, it was all about this, for this issue of constantly searching for the good that is in Yisrael and pleading for their merits constantly is a huge issue and very, very deep). So why didn't Moshe want to go on the mission to redeem the nation from slavery? Even though Moshe was completely good, he was uncertain just how far Hashem's mercies would reach: וְעַל-כֵּן גַּם מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ אַף-עַל-פִּי שֶׁהָיָה כֻּלּוֹ טוֹב לֹא הָיָה יוֹדֵעַ מִתְּחִלָּה עַד הֵיכָן מַגִּיעַ רַחֲמָנוּתוֹ יִתְבָּרַךְ עַל-כֵּן לֹא הָיָה רוֹצֶה לֵילֵךְ בִּשְׁלִיחוּתוֹ כִּי רָאָה שֶׁיִּשְׂרָאֵל יְקַלְקְלוּ הַרְבֵּה (Therefore, even Moshe Rabbeinu, even though he was totally good, he didn't know initially just how far His mercies, may He be blessed, would extend; therefore, he didn't want to go on his mission, because he saw that Yisrael will mess up a lot). Thankfully, Hashem argued with him for days and wouldn't relent. He desired to redeem the people no matter what because He had determined only to look at their good!

This is the secret of the final geulah. It all depends on seeing only the good in each and every Jew and pleading for their merits. And therefore, one must be very, very careful never to speak a word against a fellow Jew. This is exceedingly important. There are 600,000 Supernal souls of the Jewish people, and they correspond to the 600,000 Supernal letters of the Torah, for the Torah is the root of all Jewish souls. As explained in Sichot ha-Ran 91: וּכְשֶׁיֵּשׁ חִסָּרוֹן בְּאֶחָד מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל נִמְצָא שֶׁיֵּשׁ חִסָּרוֹן בַּתּוֹרָה שֶׁשָּׁם שֹׁרֶשׁ נִשְׁמוֹת יִשְׂרָאֵל כַּנַּ"ל. וְעַל־כֵּן בְּוַדַּאי אִי אֶפְשָׁר לֶאֱהֹב אֶת הַתּוֹרָה בִּשְׁלֵמוּת (When there is a deficiency in a single Jew, there is a deficiency in the Torah which is the root of the souls of Yisrael, and therefore, it becomes impossible to love the Torah completely). To the extent that we speak against our fellow Jews, we create blemishes and deficiencies in the Supernal Sefer Torah and to that extent, we will be incapable of loving the Torah. On the other hand, to the extent that we refrain from speaking ill, rather only looking for and speaking about the good in each and every Jew, to that extent we will repair the Supernal Sefer Torah, and to that extent we will be able to love the Torah more completely.

As further explained in Sichot ha-Ran 91, this is the deeper meaning of Tehillim 19:8: תּוֹרַת יְיָ תְּמִימָה מְשִׁיבַת נָפֶשׁ (The Torah of Hashem is pure, restoring the soul). When does the collective soul of the Jewish people become restored, returning to Hashem in complete teshuvah? When the Torah is pure, whole and complete. And when is that? When we neither seek for nor speak about the flaws, blemishes or deficiencies of another Jew. And that's how we merit the final geulah.

But someone may protest and say, 'But what about a Jew who is a total rasha? Certainly we aren't supposed to speak something good about him! We're not delusional. He has no good!' Well, that's exactly what all the great Sages thought about Acher, except R' Meir who thought otherwise. And that's what all the Sages thought about R' Meir, except Rabbah bar Shila who thought otherwise.

In what is probably the most famous teaching of R' Nachman of Breslov, we see these things taught explicitly (Likutei Moharan 282): דַּע כִּי צָרִיךְ לָדוּן אֶת כָּל אָדָם לְכַף זְכוּת וַאֲפִלּוּ מִי שֶׁהוּא רָשָׁע גָּמוּר צָרִיךְ לְחַפֵּשׂ וְלִמְצֹא בּוֹ אֵיזֶה מְעַט טוֹב שֶׁבְּאוֹתוֹ הַמְּעַט אֵינוֹ רָשָׁע וְעַל יְדֵי זֶה שֶׁמּוֹצֵא בּוֹ מְעַט טוֹב וְדָן אוֹתוֹ לְכַף זְכוּת עַל־יְדֵי־זֶה מַעֲלֶה אוֹתוֹ בֶּאֱמֶת לְכַף זְכוּת וְיוּכַל לַהֲשִׁיבוֹ בִּתְשׁוּבָה (You should know that one must judge everyone on the scale of merit [see Pirkei Avot 1:6], and even someone who is a 'complete rasha,' it is necessary to search and to find in him some good point, for in that little bit he is not a rasha, and by finding in him a little good and judging him for merit, one truly elevates him to the scale of merit, and one may cause him to return [to Hashem] in teshuvah).

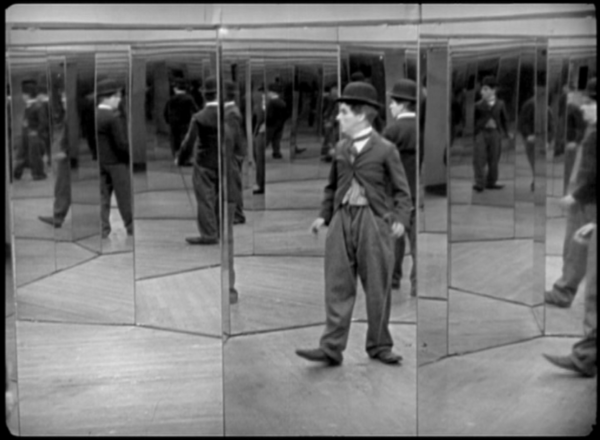

How do we know these things are true, i.e. that we must search for and find the good even in someone whom we think is a complete rasha? We learn it from Tehillim 37:10: וְעוֹד מְעַט וְאֵין רָשָׁע וְהִתְבּוֹנַנְתָּ עַל־מְקוֹמוֹ וְאֵינֶנּוּ (And yet, [there is] a little bit, and he is not a rasha, and you will think about his [previous] place, and he won't be there). Yes, there really is a little bit of good in that individual, and in that little bit, he is not a rasha. But why won't he be there when we contemplate his place? Because by searching for and finding the good, the Heavenly Court heard our advocacy, and they responded by moving him from the scale of demerit to the scale of merit, literally. This was his elevation, his aliyah. And if it's difficult to find a good point, we must keep looking because it is impossible that there isn't something good, some little mitzvah, a pleasant word spoken at some point in time…something! It's impossible that it doesn't exist. So, if we haven't found it, we must keep looking until we do find it. And in that point, he is not a rasha. Now, if we accustom ourselves to do just this—particularly with those fellow Jews who dishonour us, insult us and irritate us—what will we find? We will find the spark of their holy neshamah that emanates from the Infinite Good. And that's what we must only look at. And that's what we must keep looking at. And the more we look at it, the closer we get to it—like a spaceship approaching a distant star. And the closer we get to it, the bigger it will appear until eventually, the light of that holy soul will be so bright, so all-encompassing, that it will overwhelm and obliterate all remaining darkness. For in reality, the darkness is just an illusion anyway, for Hashem did not create us with the ability to see the flaws of others. What we are really seeing is the flaws in us that we are projecting onto others. We're really just seeing the reflection of ourselves in our own mirror.

So what do we do? We have to clean up our own act and work on removing the flaws, blemishes and deficiencies from our own lives, from our own souls. Then by default, we won't even see flaws in others. We'll automatically just see the good.

One Response

Phenomenal! Ultra deep and enlightening.

Kol tov.