A Worm, Drippings of a Honeycomb and Men of Faith

Rosh Hashanah and Breaking the Power of Imagination:

Good things come in threes: three patriarchs (Avraham, Yitzchak and Ya'akov), three mochin [spiritual brains] (chochmah, binah and da'at), three kinds of seichel [intellect] (potential, actualized and acquired), three lower aspects of the Jewish soul (nefesh, ruach and neshamah), three 'garments', i.e. manifestations, of the soul (machshavah [thought], dibbur [speech] and ma'aseh [action]), three daily prayers (shacharit, minchah and ma'ariv), three festivals (Pesach, Shavuot and Succot), and three strategies to mitigate harsh decrees like we say during Mussaf on Rosh Hashanah (teshuvah, tefillah and tzedakah). We could give more examples, but this should be enough to get us thinking. Something is built into the very fabric of the universe(s) that seems to mandate that good things come in threes.

Not only this, but each set of three is related to each other set of three. Although it would require many essays to explain this in detail, let's just take Ya'akov to illustrate the point. He corresponds to da'at, which corresponds to acquired seichel, which corresponds to ma'aseh, which corresponds to the neshamah, which corresponds to ma'ariv, which corresponds to Succot, which in turn corresponds to giving of tzedakah. We won't take the space here, but it would be worthwhile for the reader to speak out the correspondences for Avraham and Yitzchak as well.

And there's one more point worth stating up front. The third component in each set of three is the culmination or goal of the first two. For example, Ya'akov is the culmination of Avraham and Yitzchak, da'at is the culmination of chochmah and binah, acquired seichel is the culmination of potential seichel and actualized seichel, and so on. Again, it would take many essays to flesh this out in detail, but he who understands will understand.

There's also a very strange set of three enumerated in the Mishnah in Sotah 48a: מִשֶּׁחָרַב בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ בָּטַל הַשָּׁמִיר וְנוֹפֶת צוּפִים וּפָסְקוּ אַנְשֵׁי אֲמָנָה מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל (From when the ha-Beit Mikdash was destroyed, the shamir and the honeycomb ceased, and men of faith ceased from Yisrael). Let's see if we can make sense out of this set of three and see how, at least in part, it's related to the other sets of three we've outlined above.

It is written in Likutei Moharan 25:1: כִּי צָרִיךְ כָּל אָדָם לְהוֹצִיא אֶת עַצְמוֹ מֵהַמְדַמֶּה וְלַעֲלוֹת אֶל הַשֵּׂכֶל וּכְשֶׁנִּמְשָׁךְ אַחַר הַמְדַמֶּה זֶה בְּחִינַת 'שְׁרִירוּת לֵב' שֶׁהוּא הוֹלֵךְ אַחַר הַמְדַמֶּה שֶׁבַּלֵּב (Everyone must remove themselves from imagination and ascend to seichel, and when one is drawn after imagination, this corresponds to 'the vision of the heart' [sherirut lev], that he goes after the imagination that is in the heart). What is this sherirut lev that he mentions here? It is a reference to the warning that Moshe Rabbeinu gave over that describes a person who would choose to ignore the words of cursing, chas v'shalom (Devarim 29:18): וְהָיָה בְּשׇׁמְעוֹ אֶת־דִּבְרֵי הָאָלָה הַזֹּאת וְהִתְבָּרֵךְ בִּלְבָבוֹ לֵאמֹר שָׁלוֹם יִהְיֶה־לִּי כִּי בִּשְׁרִרוּת לִבִּי אֵלֵךְ לְמַעַן סְפוֹת הָרָוָה אֶת־הַצְּמֵאָה (And it would come to pass, when he would hear the words of this curse and then bless himself in his heart and say, 'Everything is going to be fine with me, even though I go in the vision of my heart [sherirut libi],' to add drunkenness to thirst).

Before we go any further, we need to clarify that the imagination being discussed here is not imagination akin to wholesome creativity. There's nothing wrong with creativity per se; and therefore, there is nothing wrong (necessarily) with ordinary imagination. Rather, the imagination mentioned above corresponds with lusts, forbidden thoughts, illusions, delusions, confusions and mental obstacles that prevent us from achieving our intended spiritual purpose. In other words, the imagination described here is another name for the Sitra Achra. This is stated explicitly in Likutei Halachot (Yoreh Deah, Hilchot Chukot Ha-Akum 2:1): שֶׁהַסִּטְרָא אָחֳרָא נִקְרָא כֹּחַ הַמְדַמֶּה שֶׁמִּשָּׁם בָּאִין כָּל הַתַּאֲווֹת וְהַבִּלְבּוּלִים וְהַמְּנִיעוֹת (The Sitra Achra is called 'the power of imagination', that from there come all the lusts, and the confusion, and the obstacles).This is a very important truth because it reveals that the Sitra Achra cannot grab hold of the kedushah of a Jew except through the imagination, as Likutei Halachot goes on to say: וְעַל-כֵּן אֵין לְהַסִּטְרָא אָחֳרָא שׁוּם אֲחִיזָה וְשַׁיָּכוּת לְפַתּוֹת אֶחָד מִיִּשְֹרָאֵל, חַס וְשָׁלוֹם, כִּי אִם עַל יְדי כֹּחַ הַמְדַּמֶּה כִּי הַמְדַמֶּה מַטְעֶה אֶת הָאָדָם שֶׁהוּא מְדַמֶּה דָּבָר לְדָבָר עַד שֶׁהוּא מְהַפֵּךְ, חַס וְשָׁלוֹם (Therefore, the Sitra Achra has no hold or affiliation to seduce a Jew, chas v'shalom, except through the power of imagination, for the imagination misleads a person to imagine one thing for another to the point that he gets everything flipped around, chas v'shalom). This is exactly the meaning of what is written in Yeshayahu 5:20: הוֹי הָאֹמְרִים לָרַע טוֹב וְלַטּוֹב רָע שָׂמִים חֹשֶׁךְ לְאוֹר וְאוֹר לְחֹשֶׁךְ שָׂמִים מַר לְמָתוֹק וּמָתוֹק לְמָר (Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil, and put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter).

This happens through the power of imagination, a power that is able to confuse the mind and turn everything on its head. It's like a person who looks at an object from a very great distance. He thinks it's one thing when, in fact, it is something entirely different. Only when he gets very close to the object does he realize that his imagination has misled him. Or it's like a person who walks through a dark alleyway at night and mistakes a tree for a person and then becomes afraid of the 'person' lurking in the shadows. It's all through the power of imagination and the power of the Sitra Achra to mislead and confuse the mind.

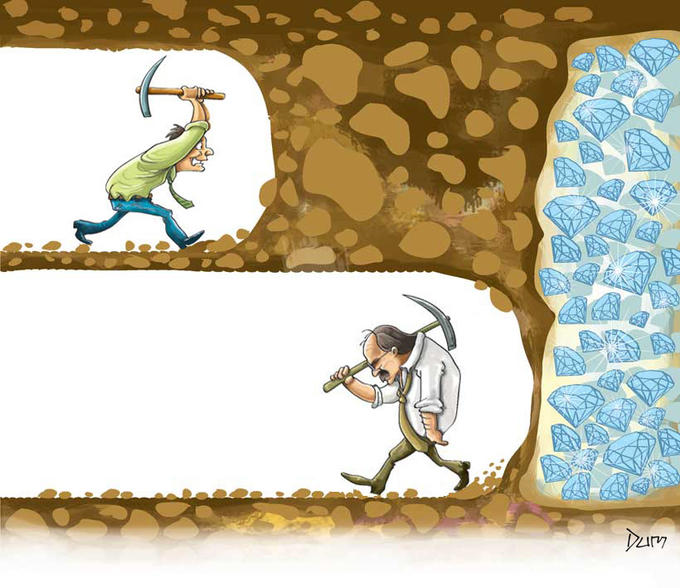

These imaginations oppose the acquisition of seichel. They are direct opposites and cannot coexist, for this is exactly what the Torah says about Ya'akov and Esav (Bereshit 25:23): שְׁנֵי גוֹיִם בְּבִטְנֵךְ וּשְׁנֵי לְאֻמִּים מִמֵּעַיִךְ יִפָּרֵדוּ וּלְאֹם מִלְאֹם יֶאֱמָץ (Two nations are in your womb, and two peoples will be separated from your insides, and one people will be mightier than the other). Rashi explains: לֹא יִשְׁווּ בִּגְדֻלָּה, כְּשֶׁזֶּה קָם זֶה נוֹפֵל (They will never be equally great [at the same time]; when one rises, the other one falls). So it is with seichel and imagination. Ya'akov corresponds to seichel and Esav to imagination. Therefore, since the imagination wars against the seichel, we must strive to rid ourselves of it.

The question is, How? Not surprisingly, three steps are needed to achieve this goal.

As explained in L.M. 25, the first step is that a person needs to remove himself from the sherirut lev and break his heart of stone (Yechezkel 11:19): וְנָתַתִּי לָהֶם לֵב אֶחָד וְרוּחַ חֲדָשָׁה אֶתֵּן בְּקִרְבְּכֶם וַהֲסִרֹתִי לֵב הָאֶבֶן מִבְּשָׂרָם וְנָתַתִּי לָהֶם לֵב בָּשָׂר (And I will give to them one heart, and I will put within them a new ruach [spirit], and I will remove the heart of stone from their flesh and give them a heart of flesh). This corresponds to machshavah, which in turns corresponds to chochmah and the first level of seichel which is known as potential seichel. It also corresponds to the shamir, a type of worm that existed during the time of the Beit ha-Mikdash that was able to split stone. Put another way, stone was subdued in the presence of the shamir. Therefore, a person who gets his heart of stone worked on by the shamir no longer follows after the lusts and the imaginations of his heart. Why not? Because the heart of stone, which is the residence of the imagination gets broken into pieces and replaced by a heart of flesh. This corresponds to teshuvah, the first one of the three strategies to mitigate against harsh decrees mentioned in Mussaf of Rosh Hashanah.

But potential seichel, i.e. machshavah, is insufficient. It must be actualized. Thoughts of teshuvah are not enough; rather, a person must draw out dibbur from the depth of his machshavah. He must use his thoughts, not just muse upon them. In a word, he must pray. And this is why tefillah is the second strategy to mitigate against or 'sweeten' harsh decrees. This corresponds to what we read in Shir ha-Shirim 4:11: נֹפֶת תִּטֹּפְנָה שִׂפְתוֹתַיִךְ כַּלָּה דְּבַשׁ וְחָלָב תַּחַת לְשׁוֹנֵךְ וְרֵיחַ שַׂלְמֹתַיִךְ כְּרֵיחַ לְבָנוֹן (Thy lips, O bride, drip like the honeycomb, honey and milk are under your tongue, and the aroma of your garments is like the aroma of Levanon). Explaining the concept of lips dripping like the honeycomb, L.M. 25:1 says: שֶׁהוֹצִיא מְתִיקוּת שִׂכְלוֹ מִכֹּחַ אֶל הַפֹּעַל (that one has brought out the sweetness of his seichel from potential to actual). This is what actually mitigates or 'sweetens' the harsh decrees. Teshuvah is great and is where we need to begin, but tefillah is better, just like kinetic energy is superior to potential energy.

The potential of teshuvah is great and the actualization of tefillah is even better, but we are still lacking if that's as far as we go. We need the third level, the culmination of seichel, i.e. acquired seichel. What is this, and why is it so important?

Acquired seichel is ma'aseh (L.M. 25:1): וְשֵׂכֶל הַנִּקְנֶה נִקְרָא מַה שֶּׁאָדָם יוֹדֵעַ הַרְבֵּה דְּבָרִים בִּידִיעָה אַחַת, כִּי קֹדֶם צָרִיךְ לֵידַע הַרְבֵּה הַקְדָּמוֹת קֹדֶם שֶׁיֵּדַע אֵיזֶהוּ דָּבָר, וְאַחַר־כָּךְ כְּשֶׁמַּשִּׂיג אֶת הַדָּבָר, מַשְׁלִיךְ הַקְדָּמוֹתָיו, וְיוֹדֵעַ אֶת הַדָּבָר בִּידִיעָה אַחַת (Acquired seichel is that a person knows lots of things in a single knowing; but before that, he needs to know a lot of introductory matters before he can know the thing. And afterwards, when he attains understanding of the thing, he can toss aside the introductory matters, for he knows the thing with a single knowing). By way of analogy, someone learning to play the violin must at first pay attention to a lot of technical details: keeping the violin under the chin and making sure it doesn't fall, holding the bow correctly, passing the bow over the strings to produce a pleasant tone instead of a scratchy noise, putting the fingers on the fingerboard in the right place in order to play in tune, producing a steady vibration with the fingers on the fingerboard to produce a warm sound, etc. It can take years to master these introductory matters, but once they are mastered, they take place automatically. They are known in a single knowing. Now when one wants to play the violin, he just picks it up and makes music. This is the meaning of acquired seichel, and that's why it's connected to ma'aseh.

Why is acquired seichel so important? Likutei Halachot explains (Choshen Mishpat, Hilchot Geviat Chov Mi'Karka'ot v'Apoteikei): כִּי כָּל זְמַן שֶׁאֵין זוֹכִין לַשֵּכֶל הַנִּקְנֶה דִּקְדֻשָּׁה אִי אֶפְשָׁר לִסְמֹךְ עַל הַשֵֹּכֶל כִּי עֲדַיִן יְכוֹלִין הַקְּלִפּוֹת, חַס וְשָׁלוֹם, לְהִתְאַחֵז בּוֹ וּלְקַלְקֵל הַשֵֹּכֶל הַזֶּה (As long as we do not merit the acquired seichel of kedushah, it is impossible to rely on the seichel because the klipot [peels that surround the fruit, forces of the Sitra Achra] are still capable, chas v'shalom, of grabbing onto it and damaging the seichel). Applying this idea to our topic, teshuvah and tefillah are both important, but they are insufficient because the klipot can still grab onto and damage the seichel. The only way to protect ourselves completely from the negative effects of the klipot of the imagination is to turn the machshavah and the dibbur into a ma'aseh. There is no other way. And this explains something very fascinating about Avraham and Yitzchak. Avraham corresponds to machshavah and Yitzchak to dibbur. As a result, the klipot were still able to grab hold of them in the form of their respective sons, Yishmael and Esav. However, what do we see regarding Ya'akov? He sired 12 holy sons, without exception. How come? How was he able to accomplish such a thing? It is because he corresponds to ma'aseh, to acquired seichel, and as we have learned, acquired seichel is the only form of seichel that is immune from the klipot of the imagination.

Therefore, it is written (Tehillim 111:10): רֵאשִׁית חׇכְמָה יִרְאַת יְיָ שֵׂכֶל טוֹב לְכׇל־עֹשֵׂיהֶם תְּהִלָּתוֹ עֹמֶדֶת לָעַד (The beginning of chochmah is the fear of Hashem, a good seichel to all those who do them, His [or 'his'] praise stands forever). What is the 'good seichel' that is mentioned here in connection with doing, i.e. with ma'aseh? It is none other than acquired seichel, for it is the only aspect of seichel that is completely good without any possibility of contamination by the forces of the Sitra Achra.

So, acquired seichel corresponds to the men of faith mentioned in the Mishnah from Sotah 48a. How so? L.M. 25:1 explains: וְעִקַּר קִיּוּמוֹ שֶׁל אָדָם לְאַחַר מִיתָתוֹ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא שֵׂכֶל הַנִּקְנֶה וְזֶה הַשְׁאָרוֹתָיו לְאַחַר הַמִּיתָה וְזֶה בְּחִינַת אֲמָנָה כִּי אֲמָנָה לְשׁוֹן קִיּוּם דָּבָר כִּי שֵׂכֶל הַנִּקְנֶה הוּא קִיּוּם שֶׁל אָדָם לְאַחַר מוֹתוֹ (The essence of man's existence after death is only the acquired seichel. This is what remains of him after death, and this is the aspect of faith [emunah], because the word emunah itself means the existence of a thing, for acquired seichel is what continues to exist of man after his death). And how do we know that emunah relates to the concept of continued existence? It is as Shlomo ha-Melech said (Melachim Aleph 8:26): וְעַתָּה אֱלֹקֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל יֵאָמֶן נָא דְּבָרְךָ אֲשֶׁר דִּבַּרְתָּ לְעַבְדְּךָ דָּוִד אָבִי (And now, O G-d of Yisrael, may Your word which You spoke to Your servant David, my father, continue to exist [ye'amen]).

In conclusion, on Rosh Hashanah when we say that teshuvah, tefillah and tzedakah remove the harsh decrees, it's not a list of options from which we get to choose. Rather, it's a three-step strategy that we must follow if we hope to nullify the harsh decrees against us individually and collectively. We begin with teshuvah, move forward with tefillah and reach the goal with a specific ma'aseh, the giving of tzedakah. Why davka the giving of tzedakah? It is because it is written (Tehillim 51:19) זִבְחֵי אֱלֹקִים רוּחַ נִשְׁבָּרָה (The sacrifices of G-d are a broken ruach), and the breaking of the imagination is the essence of bringing a sacrifice in the Beit ha-Mikdash. May it be rebuilt speedily, in our days.