Like One Man With One Heart

How to Fulfill the Mitzvah of 'You Shall Love Your Fellow as Yourself':

Commenting on the fact that Shemot 19:2 describes Am Yisrael using the plural וַיַּחֲנוּ (and they encamped) and then just two words later describes it using the singular וַיִּחַן (and it encamped), Rashi famously writes that they had achieved a level of unparalleled achdut [אַחְדוּת, unity]: כְּאִישׁ אֶחָד בְּלֵב אֶחָד (like one man with one heart). Although most of us are probably familiar with this Rashi, we may not be so familiar with the rest of Rashi's comment there, but it too deserves our attention: אֲבָל שְׁאָר כָּל הַחֲנִיּוֹת בְּתַרְעוֹמוֹת וּבְמַחֲלֹקֶת (but the rest of their encampments were with discontentment and controversy). The Mechilta d'Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai adds: ולהלן [הוא אומר] ויסעו בני ישראל ויחנו בני ישראל נוסעים במחלוקת וחונים במחלוקת וכאן הוא אומר ויחן שם חנייה אחת ניתן בלבם כדי שיאהבו זה את זה ויקבלו את התורה ([And later [it says], 'and B'nei Yisrael traveled', 'and B'nei Yisrael encamped' – traveling with controversy and encamping in controversy, but here it says, 'and it encamped there' – one encampment was given into their hearts so that they should love one another and accept the Torah).

In other words, the achdut that they experienced was an outright gift. And this is one reason why this whole episode is referred to as Matan Torah, from the word מַתָנָה [matanah, gift]. The gift wasn't just the Torah itself. Rather, it included the achdut they all experienced before they even received the Torah! And like any gift, it was not something they earned based on their collective merit. What is this comparable to? It's like a young man and young woman who 'fall in love' with other. Through no hard work or effort on their own, they automatically just see each other's good points. That's all they see. They are either completely blind to any negative character traits or unseemly flaws that their prospective spouse possess or they are just deemed irrelevant. Anyone who has been married for even a little while knows that what they experienced in their days of courtship was not natural. It was a gift, a mamash miracle. And so it was with B'nei Yisrael at the foot of Har Sinai. Their achdut was not natural. It too was a gift, a miracle. They experienced a foretaste of what Yeshayahu the Navi prophesied will be experienced once again at the time of the complete geulah (Yeshayah 55:12): כִּי־בְשִׂמְחָה תֵצֵאוּ וּבְשָׁלוֹם תּוּבָלוּן (For you will leave in simchah, and in shalom you will arrive).

How will this pasuk from Yeshayahu 55 be fulfilled? Will it happen only as a result of another unmerited miracle or will it happen this time because we make it happen? On the one hand, if we say that shalom can only come through a miracle from above and that Mashiach will bring it with him, then we're sort of 'off the hook', aren't we? We're 'in the clear', as they say, and we don't have to do anything that may be difficult to bring about this shalom on our own. Yet, if shalom can only come about this time through a bottom up approach, then we are forced to ask another question – How can it be achieved? After all, we haven't been able to pull it off for thousands of years! So now, in our generation, we're supposed to figure it out, and not just figure it out in theory, but achieve it in practice? It seems like a bit of a pipe dream. If our holy forebears weren't able to 'arrive' at Har Sinai through shalom that they themselves worked to create, is it realistic to think that we'll be able to do any better?

Regardless, it is our strong belief that we must achieve shalom from the bottom up. Although it was given as an unmerited gift the first time, now we must create it ourselves. Let's explain.

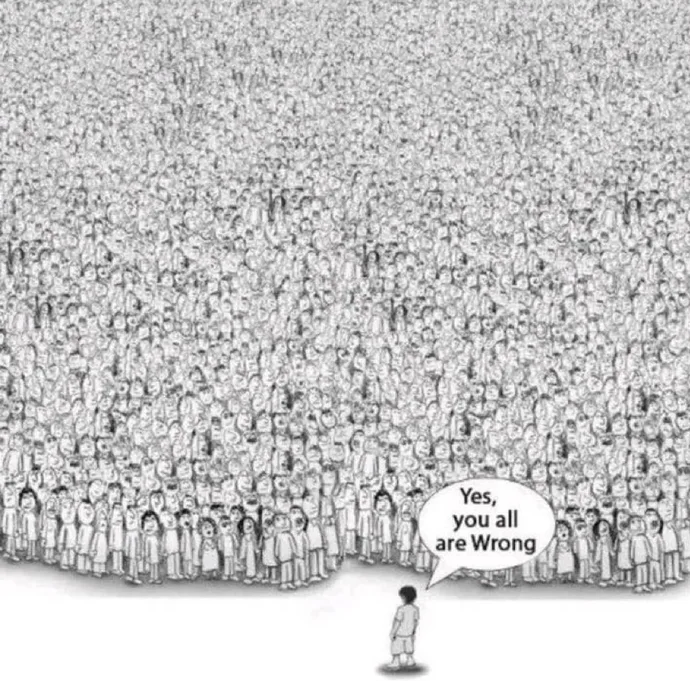

The first thing that we must acknowledge is that we have differences of opinions on almost everything. That being the case, how is it even possible to achieve achdut in the face of all of these differences of opinions? It is explained in Likutei Halachot (Hilchot Brachot Re'iah u'Vrachot Pratiot 4:4): נִמְצָא שֶׁעִקַּר הַחִיּוּת עַל-יְדֵי אַחְדוּת עַל-יְדֵי שֶׁנִּכְלָלִים כָּל הַשִּׁנּוּיִים בִּמְקוֹר הָאַחְדוּת. וְהָעִקָּר תָּלוּי בְּהָאָדָם שֶׁהוּא עִקַּר הַבְּרִיאָה וּבוֹ תָּלוּי הַכֹּל כַּיָּדוּעַ. וְעַל-כֵּן וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ הוּא כְּלָל גָּדוֹל בַּתּוֹרָה כְּדֵי לִכְלֹל בְּאַחְדוּת וְשָׁלוֹם שֶׁהוּא עִקַּר הַחִיּוּת וְהַקִּיּוּם וְהַתִּקּוּן שֶׁל כָּל הַבְּרִיאָה עַל-יְדֵי שֶׁבְּנֵי אָדָם שֶׁמְּשֻׁנִּים בְּדֵעוֹתֵיהֶם נִכְלָלִים יַחַד בְּאַהֲבָה וְאַחְדוּת וְשָׁלוֹם (The essence of being really alive is through achdut, by encompassing all the differences in the Source of achdut. And this depends upon man, who is the essence of creation, as everything depends on him, as is known. Therefore, 'You shall love your fellow as yourself' [Vayikra 19:18] is a great rule in the Torah in order to encompass in achdut and shalom, which is the essence of life, existence and the tikkun of the entire creation, people with differences of opinions coming together in love and achdut and shalom).

From this teaching, we can learn three self-evident truths. First, achdut and shalom are necessary for feeling really alive and without them there is no real life at all. Second, it is possible to fulfill the Torah's mitzvah to love every fellow Jew as oneself. And third, achdut can exist even though there are differences of opinion among us.

But someone may object and say: "Loving every Jew would mean that we're supposed to love even Jews who are criminals, rapists, pedophiles, murderers, and drug dealers, right? Well, to claim that we are supposed to love such degenerates is just ridiculous. In fact, it's insane! We're not supposed to love them. We're supposed to hate them." And such an individual could cite the very next section of Likutei Halachot to buttress his claim: וְעִקַּר הָאַהֲבָה הוּא לֶאֱהֹב אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל הַמְקַיְּמִים אֶת הַתּוֹרָה, כִּי מִי שֶׁהוּא רָשָׁע גָּמוּר בְּתַכְלִית וְאֵין בּוֹ שׁוּם טוֹב, בְּוַדַּאי מִצְוָה לִשְׂנֹא אוֹתוֹ בְּתַכְלִית הַשִּנְאָה כְּמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב תַּכְלִית שִׂנְאָה שְׂנֵאתִים. רַק עִקַּר מִצְוַת וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָמוֹךָ הוּא לְרֵעֲךָ בְּמִצְווֹת (The essence of love is to love the Jew who fulfills the Torah, for someone who is completely wicked and has no good whatsoever, for sure, it is a mitzvah to hate him with utmost hatred, as it is written [Tehillim 139:22], 'I hate them with the utmost hatred.' Rather, the meaning of the mitzvah 'You shall love your fellow as yourself' is 'your fellow in mitzvot'). So it seems like the challenger just might have a valid point. There is no mitzvah to love 'every' Jew. The pasuk just says to love 'your fellow' as yourself. And who is 'your fellow'? It is the Jew who, like yourself, does the mitzvot. And in support of this understanding, we see that David ha-Melech hated his enemies with utmost hatred!

So what's going on here? On the one hand, we cannot experience the geulah as a nation without complete achdut and shalom, and yet on the other hand, we are not supposed to love or have unity with completely wicked Jews, but only with those who do mitzvot. We seem caught betwixt and between.

Let's continue in Likutei Halachot to resolve this apparent contradiction: דְּהַיְנוּ שֶׁצְּרִיכִין לְחַפֵּשׂ וּלְבַקֵּשׁ וְלִמְצֹא בְּכָל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל אֵיזֶה זְכוּת וְטוֹב כְּדֵי לֶאֱהֹב אוֹתוֹ כְּנַפְשׁוֹ. כִּי כָּל אֶחָד מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל אֲפִלּוּ פּוֹשְׁעֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אִי אֶפְשָׁר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אֵיזֶה צַד טוֹב וּזְכוּת וְכַמְבֹאָר עַל פָּסוּק וְעוֹד מְעַט וְאֵין רָשָׁע וְכוּ' עַיֵּן שָׁם בְּסִימָן רפב בְּליקוטי מוהר"ן (We need to search, request and find in each and every Jew some merit and good in order to love him as one's own soul, for it is not possible that there isn't some good side or merit in every Jew, even in Jewish criminals, as explained in Likutei Moharan 282 on the pasuk, 'And yet, [there is] a little bit, and he's not a wicked person, etc.').

R' Nachman's famous teaching, popularly known as Azamra – 'I will sing', explains at length how there are no longer any completely wicked Jews. These are his holy words: דַּע כִּי צָרִיךְ לָדוּן אֶת כָּל אָדָם לְכַף זְכוּת וַאֲפִלּוּ מִי שֶׁהוּא רָשָׁע גָּמוּר צָרִיךְ לְחַפֵּשׂ וְלִמְצֹא בּוֹ אֵיזֶה מְעַט טוֹב שֶׁבְּאוֹתוֹ הַמְּעַט אֵינוֹ רָשָׁע וְעַל יְדֵי זֶה שֶׁמּוֹצֵא בּוֹ מְעַט טוֹב וְדָן אוֹתוֹ לְכַף זְכוּת עַל־יְדֵי־זֶה מַעֲלֶה אוֹתוֹ בֶּאֱמֶת לְכַף זְכוּת וְיוּכַל לַהֲשִׁיבוֹ בִּתְשׁוּבָה (You should know that one must judge everyone on the side of merit [Pirkei Avot 1:6], and even someone who is 'completely wicked,' it is necessary to search and to find in him some good point, for in that little bit he is not completely wicked, and by finding in him a little good and judging him for merit, one elevates him to the side of merit and causes him to return [to Hashem] in teshuvah).

We have a responsibility not only to seek, but to request (in prayer) to help us achieve what we seek, and not to give up on this quest until we actually find some good or merit in every Jew, even in the worst criminals – obviously we are referring to Jews with whom we are personally acquainted. It is not good enough just to look casually and then say, 'Well, I tried. I can't find any good in that piece of garbage over there. I did what is required of me. I'm patur now.' No, we have to keep looking and keep praying until we find the speck of good within him. Because in that speck of good is the light of the Ein Sof Who is the Root and Source of All Good. And isn't it ironic that Reish Lakish, who himself was a former Jewish criminal, was the one who had to teach us this very point (Chagigah 27a): פּוֹשְׁעֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁמְּלֵאִין מִצְוֹת כְּרִמּוֹן דִּכְתִיב: ״כְּפֶלַח הָרִמּוֹן רַקָּתֵךְ״, אַל תִּקְרֵי רַקָּתֵךְ אֶלָּא רֵקָנִין שֶׁבָּךְ (Jewish criminals are full of mitzvot like a pomegranate, as it is written [Shir ha-Shirim 4:3]: 'Your temple is like the slice of a pomegranate.' Don't read 'Your temple [rakateich]' but rather, 'The empty ones that are in you [reikanin she'bach]').

Now we should be able to grasp the essence of love itself. Continuing in Likutei Halachot: כִּי עִקַּר הָאַהֲבָה הִיא כְּדֵי לְקַשֵּׁר עַצְמוֹ עִם הַטּוֹב שֶׁבְּכָל יִשְׂרָאֵל וְלִכְלֹל עִמָּהֶם יַחַד בְּאַהֲבָה וְאַחְדוּת כְּדֵי לְבַטֵּל כָּל הַשִּׁנּוּיִים וְלִכְלֹל בְּאֶחָד הַפָּשׁוּט יִתְבָּרַךְ, שֶׁמִּשָּׁם כָּל הַחִיּוּת וְהַקִּיּוּם וְהַתִּקּוּן שֶׁל כָּל הָעוֹלָמוֹת כַּנַּ"ל. כִּי עַל-יְדֵי קִיּוּם הַתּוֹרָה וְהַמִּצְווֹת נִתְקַשְּׁרִין וְנִכְלָלִין כָּל שִׁנּוּי הַדֵּעוֹת יַחַד (For the essence of love is in order to connect oneself with the good that is in each Jew and to be included in them together in love and achdut in order to nullify all the differences and to be encompassed in the Simple Oneness, may He be blessed, that from there comes all life, existence, and tikkun of all the worlds [as we saw above], for by fulfilling the Torah and the mitzvot all the differences of opinion are connected and included together).

This is very important because it helps dispel a false notion that blocks us from properly loving each other. We tend to resist the notion of loving every Jew because, admittedly, maybe we don't like the personalities of certain others, or maybe because we tend to see only the bad characteristic traits in others, or maybe because we find the appearance of others to be offsetting or even repulsive. But that's missing the point entirely. The focal point of one's love is the good in the other. We have to work on ignoring those things that irritate or annoy us. Suppose, for example, a fellow Jew constantly insults you, or has repulsive body odor, or is loud and obnoxious in shul, or you have heard that he has done despicable things. The gut reaction is to focus on the negative. But what if that person is a close relative, maybe even a son or a daughter? Would we not have another motivating factor, perhaps even a mitigating factor, to override that gut reaction? Of course we would. And so that's how we have to deal with each other. We're not saying that we are suppose to justify reprehensible behavior. Not at all. Rather, for the sake of the mitzvah of 'You shall love your fellow [Jew] as yourself,' we must focus on the point of good because the point of good is something which one can love. And that's how we create achdut in the face of otherwise incalcitrant differences of opinion, personality, lifestyle and behavior.

And this explains, at least one reason, why Hashem gave us the Torah. Think about it. If B'nei Yisrael had already achieved the ultimate achdut and shalom before they received the Torah – which they had – then why did they need the Torah? Hadn't they already fulfilled the very purpose of the Torah? That's a bit of a conundrum, isn't it?

The answer is that Hashem gave us the Torah because the achdut and shalom that we had at Har Sinai was not natural. It wasn't something that we worked on to create. It was a gift, a miracle. We hadn't earned it. And so, Hashem knew, in His all-encompassing wisdom, that it wouldn't last. Therefore, He gave us the gift of the Torah so that we could do mitzvot in order that there would be a point of good in each of us, in order that there would be a source for love in each us, in order that we could connect to each other in unity through that source of good, in order that our natural differences would dissolve away in the Infinite Oneness, in order that we would eventually earn achdut and shalom on our own, in order to merit the ultimate and final geulah.

Now go find yourself an isolated place or even a closed room where you feel comfortable, and consider that fellow Jew that you really don't like. Surely, he has some mitzvah to his credit. Don't focus on what you don't like. Just search and seek and find the points of good. Speak them out loud. Don't just think about them. Actually speak them out. That's our avodah to bring Mashiach.