In last week’s article, we explained how tefillah [תפילה, prayer] is Mashiach’s fundamental weapon for defeating the forces of the Sitra Achra. By extension, we learned that this is also the weapon that each and every one of us must use to defeat the forces of evil in our lives. We ended that article by saying that no opposing force can stand in the way of this weapon when it is wielded properly. In this article, we will ask and answer two follow up questions. First, how does one acquire this weapon of tefillah? And second, how does one wield this weapon properly?

Let’s start with the first question. How does one acquire tefillah powerful enough to use as a weapon with which we can fight (and win) all of the true battles we face, battles rooted not in the physical world, but rather in spiritual forces? R’ Nachman states (Likutei Moharan 2:2): וְזֶה הַכְּלִי־זַיִן צָרִיךְ לְקַבֵּל עַל־יְדֵי בְּחִינַת יוֹסֵף הַיְנוּ שְׁמִירַת הַבְּרִית (This weapon must be received through the aspect of ‘Yosef’, i.e. guarding the covenant [brit]). What does it mean that we need to be in the aspect of Yosef? As is known, Yosef corresponds to the sefirah of yesod, which corresponds to one’s physical brit. Each man must be very careful never to blemish his brit, but if one has stumbled in the past and blemished it, he needs to cease causing further damage to oneself and to all the worlds, and then do complete teshuvah. Granted, this is a very serious undertaking, but if one is able to make progress in this area, he will grow much closer to Hashem.

One of the many proofs that we could bring down for being shomer brit leading to tefillah comes from Tehillim 45:4: חֲגוֹר־חַרְבְּךָ עַל־יָרֵךְ גִּבּוֹר הוֹדְךָ וַהֲדָרֶךָ (Gird your sword upon your thigh, O warrior, your majesty and glory). What is this sword? As we learned last week, the sword that was of concern to David ha-Melech wasn’t physical in nature, but rather spiritual, i.e. tefillah. And where is it to be found? It’s bound to the thigh, which is the place of one’s brit. By guarding one’s brit, i.e. one’s thigh, one becomes a true warrior, as we see with Yosef. Although the wife of Potiphar attempted to seduce him numerous times and wanted him to stumble in this area, he remained steadfast. She cast her eyes upon him, but he refused to cast his eyes upon her, as it is written (Bereshit 39:7): וַיְהִי אַחַר הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה וַתִּשָּׂא אֵשֶׁת־אֲדֹנָיו אֶת־עֵינֶיהָ אֶל־יוֹסֵף וַתֹּאמֶר שִׁכְבָה עִמִּי (And it came to pass after these things, and the wife of his master ‘lifted up her eyes’ to Yosef, and said, ‘Lie with me’). And what is the very next word in the Torah? וַיְמָאֵן (And he refused). It wasn’t just that he refused to lie with her. That’s obvious as the continuation of the story confirms. The point is that he refused even to look at her. Nothing she did could cause him to look at her. And this drove her absolutely crazy! Not only that, but after he was made second to Pharaoh, riding in the royal chariot, he never once looked upon the face of any of the Egyptian women who climbed over the walls and threw their jewelry at him in order to attract his attention (Bereshit 49:22): בֵּן פֹּרָת יוֹסֵף בֵּן פֹּרָת עֲלֵי־עָיִן בָּנוֹת צָעֲדָה עֲלֵי־שׁוּר (Yosef is a man of grace, a man of grace because of the eye, [even as] daughters, i.e. young Egyptian girls, stepped up onto the wall to get a look at him [translated based on Rashi]). This is the aspect of Yosef about which R’ Nachman is teaching. And when a man reaches this level of care with his eyes, and by extension, with his brit, i.e. becoming a truly modest individual, he is given the powerful gift of tefillah.

But how do women acquire this awesome and powerful weapon of tefillah? What does it mean for a woman to be shomer brit? As we already mentioned, the male’s brit is rooted in the sefirah of yesod. But females are also created in the image of G‑d; and therefore, they also have an aspect of yesod or brit which pertains to the same fundamental attribute. And what is that? For both men and women, it is really the same thing. Being shomer brit means being kadosh, i.e. holy. And for women, this would correspond to the very opposite behavior of Potiphar’s wife. It means being modest in every true sense of the word—in thought, conduct, and appearance, i.e. not dressing or behaving in any way to attract the gaze of men.

Interestingly, we can see this parallel between men and women if we compare Yosef with Esther. Even as Yosef was associated with the attribute of grace—Rashi says that בֵּן פֹּרָת [ben porat] means בֶּן חֵן [ben chen]—Esther was also associated with the attribute of grace (Esther 2:15): וַתְּהִי אֶסְתֵּר נֹשֵׂאת חֵן בְּעֵינֵי כׇּל־רֹאֶיהָ (And Esther carried [herself] with grace in the eyes of all who saw her). And this aspect of true grace comes only through purity, holiness and modesty. This was true of Esther even as it was true of Yosef.

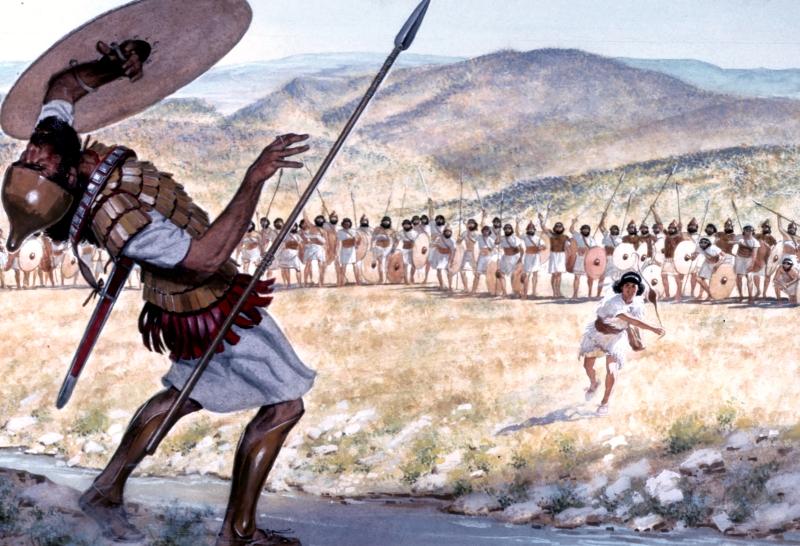

Now that we understand how one acquires the weapon of tefillah, we can now move on to our second question. How do we wield the weapon properly? By way of analogy, we are all capable of picking up a weapon such as a gun or a knife, but that doesn’t mean that we know how to use them well or that we have ever been trained in the proper use. The same is true of tefillah. Just because most of us pray, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re experts at it. To address this issue, R’ Nachman quotes from Shofetim 20:16, a verse that immortalizes the unique skill of 700 hand-picked warriors from the tribe of Binyamin, all left-handed: כׇּל־זֶה קֹלֵעַ בָּאֶבֶן אֶל־הַשַּׂעֲרָה וְלֹא יַחֲטִא (each one being able to sling a stone [with a slingshot] at a hair and not miss). Is this just an interesting tidbit of history, or is there a deeper meaning, i.e. a spiritual meaning, to it?

As is known, there are ‘left’, ‘right’ and ‘middle’ ‘columns’ to the structure of the upper lights, i.e. the sefirot. The right column is controlled by the attribute known as chesed (kindness, love, giving), the left column by the attribute of gevurah (severity, strictness, judgment), and the middle column by tiferet (which encompasses truth, justice, beauty, etc.). Therefore, the explanation of Shofetim 20:16 is as follows (L.M. 2:3): וְזֶה אִי אֶפְשָׁר אֶלָּא עַל־יְדֵי בְּחִינוֹת מִשְׁפָּט כִּי מִשְׁפָּט הוּא עַמּוּדָא דְּאֶמְצִעוּתָא הַיְנוּ שֶׁקּוֹלֵעַ עִם כְּלֵי זֵינוֹ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם הַצָּרִיךְ וְאֵינוֹ מַטֶּה לְיָמִין וְלֹא לִשְׂמֹאל אֶלָּא לָאֶמְצַע (And it is impossible [i.e. to use this weapon correctly] without the aspect of mishpat, for mishpat is the middle column, i.e. that one hits the target with his weapon not veering off either to the right or to the left, but rather to the middle). Obtaining true justice is what mishpat is all about, getting right to the heart of the matter without letting other considerations such as feelings, affiliations, biases, etc. cloud the issue. Therefore, mishpat, which is just another term for tiferet or rachamim [mercy], which is in the middle between the two extremes of chesed and gevurah, incorporates both strictness as well as kindness. It elucidates the deep truth of the matter. It does not seek to extend chesed more than is appropriate (and certainly not to those who are cruel), nor does it seek to be overly strict upon people who do not deserve it. This is the deeper meaning of the verse (Tehillim 112:5): טוֹב־אִישׁ חוֹנֵן וּמַלְוֶה יְכַלְכֵּל דְּבָרָיו בְּמִשְׁפָּט (Good is the person who graciously gives and lends; he shall conduct his affairs with mishpat). The words ‘his affairs’ could literally be translated as ‘his words’, i.e. his words of tefillah need to be accordance with mishpat. One must make sure to hit the middle column of mishpat with his words of tefillah.

You may wonder why this is so important. What difference does it make if I veer to the right or the left? Bear in mind that tefillah is an exceedingly powerful weapon. Maybe we don’t think about it like this very often, but in the hands of someone who is an expert at tefillah, it must be wielded very carefully. If one’s prayers are on a high level, one must ensure that he hits the target every time. If not, he could cause serious collateral damage in his tefillot. This is not a trivial thing.

Is there anything we can do in a practical sense to get better at wielding the slingshot? Like most everything in the Torah, thinking alone won’t get us to the goal; we need action. After all, we live in the world of Asiyah, the world of Action. Just as we learned that being shomer brit is the action needed to obtain the weapon of tefillah itself, we need to know what action is needed to obtain the skill needed to wield the weapon like a skilled warrior.

R’ Nachman answers our question (L.M. 2:4): וְעַל יְדֵי מָה זוֹכֶה לִבְחִינַת מִשְׁפָּט? עַל יְדֵי צְדָקָה שֶׁעַל יְדֵי צְדָקָה אוֹחֲזִין בְּמִדַּת הַמִּשְׁפָּט כְּמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב צִדְקַת ה’ עָשָׂה וּמִשְׁפָּטָיו וּכְמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב מִשְׁפָּט וּצְדָקָה בְּיַעֲקֹב וְכוּלוּ (And through what mechanism does one merit the aspect of mishpat? It is through the giving of charity [tzedakah], that through tzedakah one grabs hold of the attribute of mishpat, as it is written [Devarim 32:21], ‘He [i.e. Moshe Rabbeinu] did the tzedekah of Hashem and His mishpat…’, and as it is written [Tehillim 99:4], ‘Mishpat and tzedakah in Yaakov [You did], etc.’). We learn at least two important truths here. First, Moshe Rabbeinu was able to be such an amazing judge and aim his tefillot accurately to guide Hashem’s nation properly because he was generous and gave tzedakah even as Hashem gives tzedakah. Second, these two attributes of mishpat and tzedekah are intimately woven together. And as the expression goes, ‘you can’t have one without the other’. This is why they are mentioned together at the end of the 11th berachah of the Shemoneh Esreh: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְָי מֶלֶךְ אֹהֵב צְדָקָה וּמִשְׁפָּט (Blessed are You, Hashem, King Who loves tzedakah and mishpat). Tzedakah leads to mishpat.

This explains the reason behind the giving of tzedakah before praying. It is not merely so that our tefillot will be heard when they are preceded by a mitzvah, nor is it because in wanting to arouse the attributes of kindheartedness and charity in Hashem we need to behave similarly (in the aspect of middah k’neged middah). Although those are both true reasons, the deeper reason is that by giving tzedakah our hands learn to shoot straight so that we don’t miss the target. This is what David ha-Melech meant when he said (Tehillim 144:1): לְדָוִד בָּרוּךְ יְָי צוּרִי הַמְלַמֵּד יָדַי לַקְרָב אֶצְבְּעוֹתַי לַמִּלְחָמָה (Of David, Blessed is Hashem, my Rock, Who teaches my hands for battle, my fingers for war). He wasn’t praising Hashem because he went to West Point or joined Sayeret Matkal. He was praising Hashem because he learned how to pray with sublime skill. Isn’t that an awesome truth! But don’t misunderstand; the giving of tzedakah in order to improve our shooting skills is not limited to the time period right before we step forward in Shemoneh Esreh. Anytime we give tzedakah we are able to tap into this wellspring of mishpat which brings us added skill in praying accurately.

In summary, we have learned that our wars (and the wars of Mashiach) are not fought with physical weapons, but rather with the spiritual weapon of tefillah. This weapon is not easily acquired; it requires a lifelong commitment to personal purity, i.e. guarding one’s eyes and brit against defilement, dressing modestly, and not seeking physical attention. And even with these commendable attributes to our credit, we may still fall short of perfect tefillah if we find ourselves sunk in the desire for money. Therefore, with G‑d’s help, we plan to follow up on this point in the near future.

Leave a Reply